In Conversation w. Georg Petschnigg

Athletics welcomes you to the year’s first edition of In Conversation, our series of discussions with colleagues and friends of the studio.

We’re joined by Georg Petschnigg, the Head of Product Design at The New York Times. Over the last two decades Georg has worked on a wide range of projects and products that have changed the way we play, collaborate, and create. At Microsoft, Georg was part of Pioneer Studios, the creative lab that developed groundbreaking products like Courier, Kin, and what eventually became the Hololens Zune. Later, he founded tech company FiftyThree, building iconic tools for creativity and innovation including the award-winning immersive sketching app Paper, the digital stylus Pencil, and the team collaboration product Paste. FiftyThree and it’s products were later acquired by WeTransfer, where Georg became the General Manager and Chief Innovation Officer. At WeTransfer, George led the company from a single-product platform to a multi-product portfolio. Georg is now applying his acumen at the intersection of art and technology to that invaluable arbiter of truth: The New York Times. That’s where we find him today.

Malcolm Buick (Athletics): Where in the world is Georg Petschnigg this week?

Georg Petschnigg (The New York Times): Miami!

MB: We’ve known each other for almost two decades and have had the opportunity to collaborate on a number of projects in what I’d call the “work smarter” space, that intersection of technology and creativity. I’ve always looked to you because you’re so good at bringing groups together within an organization and creating an amazing design culture, as with Pioneer Studios, Microsoft, FiftyThree, and more. It’s always been fascinating to be on the other side of that and working with you.

GP: I am a technologist at heart. I studied engineering and computer science, but very soon I started realizing that all of this technology needs to serve something. Technology doesn’t exist for technology’s sake. And for me, it’s always been in the pursuit and the service of creativity. For me, that’s the joy of living. You get to create and shape your life, and life is a really, really beautiful thing.

I started seeing this when I was at the Bell Labs working on HDTV. When I saw these HDTVs, I thought this was like the moment where people would see postcards from all over the world. In high-resolution they would fall in love with the world because it’s so stunning to look at, when you see The Grand Canyon in high-resolution, and even animal videos and sports videos. You were right there in the arena! It was one of those really exciting moments, and it’s a good reminder [how fast things change] that HDTV is considered low resolution today.

From there I ended up working on digital cameras, computational digital photography, then made my way into productivity tools. These are essentially tools that augment human capability, like writing faster or adding numbers faster working on the Office suite. That was exciting, but I ended up noticing the limitations of productivity. This is where I made the move towards creativity. Productivity has a diminishing return. At some point you just can’t get more efficient.

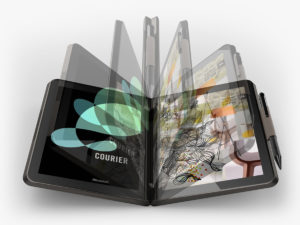

Instead of finding a faster way, you gotta find a better way, and that’s where creativity comes into play. That ended up being, for me, the next level where technology could go. How could we actually create and build tools for creativity? And that’s one of the big first projects you and I worked on around that time — Courier, which was at Microsoft. This was – pre-iPad – a dual screen tablet. Now we have the language to describe it: a foldable tablet! It really embraced this idea of creating a space for thinking, for thought, for creation. It was a revolution against the espresso experience of the mobile phone, where this mobile phone was always on the go, it was this loud place, and we thought: what if we could create more of a whiskey or wine experience with Courier? Courier opened my eyes to the importance of brand, because as these technology projects were getting larger and larger in scope, we began building hardware and online services, and had to think through go-to-market strategies, retail offerings, and developer platforms.

These projects ended up getting just so huge, and that’s where I started realizing that brand in itself and brand development is just an incredible tool to bring an organization together and to manage complexity. Ultimately, how do you create an experience that feels that it came out of a common hand? The approach was to get at the soul of these projects, and brand design in particular is just really, really good at that. Because it’s almost like a great brand designer is a great therapist. Great brands can reflect back to you who you want to become, or who you are, or where you’re headed.

When you get that balance right, you’ve created a shared spiritual language between the engineer, the designer, the marketer, the material scientist, the hiring manager, and the recruiter. And all of a sudden, everyone can start speaking a similar language or seeing a similar direction. That’s something that brand brought to the fore. And that’s something that we embraced, of course with FiftyThree and my next company. And that’s why you and I have always stayed in touch, because we’ve always worked at the frontier of new products, where companies are evolving their brand.

A great brand designer is a great therapist. Great brands can reflect back to you who you want to become, or who you are, or where you're headed.

MB: I really do feel like with Courier we were probably a decade or so ahead of the market, considering how active the intersection of creativity and technology is right now. 10, 15 years ago, it was about productivity — speeds and feeds — always working toward how fast you can go, how efficient you can be, like GO, GO, GO! You were instead evangelizing this idea of creativity. It’s really become the zeitgeist right now. And this was the central premise of Pioneer Studios, which was indeed pioneering. As I understand it, Microsoft curated a core group of creative people — technologists, engineers, writers, philosophers, you name it — and gathered you all in a building in downtown Seattle, nestled amongst the cool “bread-break” sort of creative spaces.

GP: You gotta give credit to Jay Allard, Albert Shum, Ray Riley, and all the various folks that were involved in Pioneer Studios. One of the big ideas behind Pioneer Studios was actually to get design, in many ways, to escape velocity. When I started at Microsoft, there was like one designer for every 40 engineers, and it was just really difficult for design, at a certain level, to make it into orbit, to reach the escape velocity that it needed. Through Pioneer Studios, it was a clear attempt to start venture product development with a very strong design focus out of the gate. And it did shift, it just changed things dramatically. We ended up building and envisioning AR experiences that became the HoloLens. We worked through new mobile phone experiences, and Courier, and it also gave us a chance to really understand how to approach brand-centered product development.

MB: And from there, you created your own product company, FiftyThree, where we crossed paths again and explored this subject of creativity with two products: Paper and Pencil. Tell us about that.

GP: I ended up starting FiftyThree with a couple of folks that I had met at Pioneer Studios: John Harris and Andrew Allen. We later recruited Julian Walker into the mix. We founded FiftyThree because we wanted to take that ethos to the next level: the truly brand-centered product development, where we could really focus on using technology to advance creativity. That was all we wanted to do.

One of the great things with a start-up, or a new venture of that type is that it is quite risky. It’s definitely not as safe as a steady paycheck you’d get from a large corporation. But the thing that you gain is an intensity of focus. I was excited to focus on working with my founding team. I thought the world of them — still do — and felt like the worst, worst case is that I would look back on this time as one of the greatest learning experiences alongside some of the people I respected the most. And the second thing is this idea of thinking through how we can use technology to advance creativity. We were able to do that 24/7.

That’s even where the brand idea of FiftyThree came from. FiftyThree centimeters is the length of an average arm’s reach: the space between head, heart, and blank canvas, where creation happens. The first product fittingly was called Paper, because that’s where ideas begin. One of the big breakthroughs of Paper was the idea of introducing and creating a gestural sketching and drawing program that would imbue the drawer with superpowers. We took some of the aesthetic intelligence that Andrew Allen would have when he would use watercolors or a calligraphy bush, and developed algorithms to actually replicate that and balance it carefully so that you could move from an experience that felt very supportive and almost game-like to one for tremendous artistry and mastery.

One of the things that came out of that working model of having designers and engineers working together was a strong brand ethos from the get-go, directed towards a problem. With John Harris in the mix, we also had the hardware product in mind, because we knew for any type of big platform breakthrough, you need to design the software and the hardware together. So while we were creating Paper, we also were creating Pencil, which became the top selling digital stylus and really set the standard for how digital styli should work. There are no buttons on it, you have a fine tip to write, you have a side to shade, and you can flip the device around to erase.

It really embraced gesture creation. With styli at that time, people didn’t even know that they should be on devices. There’s that quote from Steve Jobs I’ve heard so many times: “If you see a stylus on a device, you really blew it.” But the reality is that we felt like human hands had evolved to the point that you can actually use tools quite effectively, and created a set of innovations around sketching, and the use of the stylus.

There’s that quote from Steve Jobs I’ve heard so many times: “If you see a stylus on a device, you really blew it.” But the reality is that we felt like human hands had evolved to the point that you can actually use tools quite effectively, and created a set of innovations around sketching, and the use of the stylus.

MB: It was a beautiful object, too. And the identity, with the texture of the wood, and the pencil, and the packaging that it came in, the whole package was really considered. I’ve always believed you’re an engineer at heart, but you have such a sharp perspective on design quality at all levels.

GP: The idea of producing the walnut pencil came from John Harris. John said: if we’re gonna get the stylus thing right, we gotta do it with a warm material. Part of the experience is that it’s human, it’s approachable, and it’s warm. It shouldn’t be plastic, it shouldn’t be cold metal. From there, you’re limited to a set of materials. So wood became it and I fought that decision because I knew the manufacturing cost [laugh]. I knew that when you’re manufacturing this thing and shipping, like, a wooden pencil across the Atlantic, things break. I slept on it for one night and then just called him back and said “John you’re right. We gotta do it. We have to absolutely do it. We will move engineering and packaging, whatever we need to make this a reality.” And it’s a funny story because later, Laurene Powell Jobs invested in the company and I had a chance to present Pencil to her. And her reaction actually was like, you know, “Steve [Jobs], would’ve loved this.” And this is literally what she said: “This is no longer a stylus. This is something else.” So that was actually really, really cool to hear.

MB: Wow. Among you and your team at FiftyThree, there was a lot of joy in your work, and an infectious, energetic quality to your process. It was always done in a way that was very conversational and community-based. It felt quite different. That’s something you brought to the table and to this space. I’d love to hear a little bit more about that. Is that just who you are, or was it by design?

GP: It wasn’t necessarily planned. I can tell you, this is one of the values that we deeply invested into FiftyThree. We said when we started that there were a few things that are important to us. It’s about craft, collaboration and kindness. That was a really, really important piece to us because we knew there would be a moment where we will all run into a dead end and we’ll have to lean on each other. It’s kindness that supports the other two. You know, kindness is sort of this understanding that when you’re trying out new things, especially in the creative process, it’s just not gonna always work out, and you need to have a certain humility and kindness to it. And that’s a great starting point.

I’m deeply grateful for the people that I got to work with over the course of my life. If there is something that I added, I think I was born with an overdose of enthusiasm [laugh] and I don’t know when it’s gonna run out. I hope it’s never gonna run out. But it’s one of those pieces where I’m just like, wow, there are just so many incredible things you can discover in the details and the nuances and the stories. And I would keep telling the teams that there’s no greater feeling than standing at the right frontier with the right team and taking the next step forward, together. And I had the opportunity to do that, from digital TVs, to cameras, to productivity tools, to tablets, to WeTransfer. With WeTransfer, we did it with our subscription service for creative collaboration. And now at The Times, it feels like there are incredible opportunities along the way.

There's no greater feeling than standing at the right frontier with the right team and taking the next step forward, together.

MB: You’ve been at The New York Times for a year now as Head of Product Design. Again, you’ve always been at the forefront of technology and creativity, and now Athletics has the good fortune to work with you on a small project around the next generation of brand advertising in digital. We loved working with you, and your team is super exciting.

GP: Actually, some feedback on that project: every time people see this work, even people from the newsroom are saying “I never would’ve said this, but these are great ads.” People are saying, these are great ads! People are excited about it [laugh] and I was like, yes, that’s what we’re trying to achieve, where people look at this work and they’re like, whoa, these look really compelling.

MB: That’s exciting to hear! What drew you to The Times and what are some neat things you’re thinking about for the future?

GP: My journey from productivity to creativity to now — the source of it all — is just curiosity and being deeply curious about the world around you. Think about the mission of The Times: it seeks truth and helps people understand the world. I love that. That there’s actually an organization that’s a general interest publication which is going to go out there with their over 2,000 journalists and turn over stones and go the distance to deliver stories that help people understand the world and therefore inform their curiosity. I like that. There are a couple things that we’re on the precipice of.

The first one is not just helping people understand the world, but also helping people engage with it. This is where journalism gets to leave the page and becomes alive in our communities and digital communities. This is a huge challenge and opportunity.

The second thing links back to my personal journey, when I started realizing that I was drawn to technology in the nineties, particularly the Internet. It had this incredible promise of making knowledge more accessible. There was this promise of the knowledge economy, the information highway, and somewhere along the way something went wrong. All of a sudden we’re talking about misinformation and people are more scatter-brained than ever. The dialogue online just doesn’t feel nuanced. If you start out from the sort of promises that the interconnectedness of people could have brought — richer understanding of each other — it doesn’t feel that way. It feels way more scatter-brained. It feels more polarized than ever. I don’t think people have changed. People are still generally good, they’re generally curious, they’re enthusiastic. People are awesome, right? But a lot of the mediums that we’re dealing with do not promote that.

Having worked on things like Internet Explorer and these platforms, I know what went wrong. If you look at the launch of every new big platform — Google, Facebook, Twitter — they all will feature the news first, because people are drawn to it. What went wrong is that in an effort to aggregate information and present the news, everyone ended up presenting the news in this very reductionist way of headline image and text. Since the nineties, up until now, at the point of aggregation the news presentation would not include things like data tables, video playback, or sound.

So the way the news has been presented in search engines or feeds has created a really reduced view of what the news could be doing for you. Where I see a huge opportunity is to upend that, open it up and really change people’s perception of the role the news can play in our lives and how it should feel in its presentation. So with The Times there’s a really big opportunity to do that.

I don't think people have changed. People are still generally good, they're generally curious, they're enthusiastic. People are awesome, right? But a lot of the mediums that we’re dealing with do not promote that.

MB: Amazing. To work for a company that has a mission of helping readers understand the world, you’re absolutely at the right place.

GP: Exactly, and I think it requires a much richer presentation. It’s not just words, it’s words and images and video and stories. Like Steve Duenes, who we get to work with often, says: “we need to find the right format the story deserves.” It’s not just one particular media type, it’s the right media types to tell the best story possible, and then you get to words. Then you get to a vision of journalism in the news and richness around it that aligns with the richness and the vibrancy of life and how we experience it. And it isn’t just this headline versus that headline. My 280 characters versus yours. My two minute video versus yours. No! Create, capture as much of the human experience needed to really convey the point.

I’m still holding onto my vision of a much more multicolored world. People can fall in love with the information and beauty and complexity that life has. It’s not always easy, but it starts by having a much richer view and corpus of information that you’re dealing with. So that’s sort of the opportunity that we have at The New York Times. We get to tell these stories in a much richer way, and we get to build the products that house them, and we get to create this wider, broader range of the news. So it’s exciting. It’s really, really incredible and exciting.

I'm still holding onto my vision of a much more multicolored world. People can fall in love with the information and beauty and complexity that life has.

MB: I’ve known you a while now and I get a sense of your bubbling excitement there. So it’s great to hear that you’re happy and feeling fulfilled and energized. I have one last point to make, if I may. Years ago you told me about your family owning a castle and how you would joust at the castle. Ostensibly, you were a knight and you would charge into these jousting battles here, there, and everywhere. And that, for me, is the image of how you’ve progressed through your creative technology career: head in there, lance up charging towards the unknown to a certain extent. So I love that analogy and maybe you want to talk a bit about your jousting past.

GP: [laugh] I should correct that. It isn’t jousting. I was more into sword fighting or blindfolded egg dancing [laugh]. You need to keep these things separate [laugh]. Jousting is dangerous. It’s really, really dangerous. I wouldn’t recommend it. Sword fighting and fencing is okay. You can wear protection. But in many ways what these jobs require is to do whatever it takes to preserve a crumbling castle in Germany [laugh]. Whatever the job took. That’s what we signed up for.

MB: Georg, thank you so much for your time, and insight. Always inspiring to speak with you and hear what you’re up to. Looking forward to many more projects to come.

This interview was edited for length and clarity

For more pieces like this, subscribe to Athletics Quarterly